Winemaking

My label for my last amateur wine - Eleven (a la Spinal Tap). We actually considered naming our winery Eleven, which would have been a mistake, because there is an Eleven Winery on Bainbridge Island! (After "going to eleven" a bicycle racing term). Since then, there is now a Row Eleven, E11even, and Eleven Eleven wineries (all in California) !

Winemaking Philosophy

Spinal Tap lead guitarist, Nigel Tufnel explains the importance of going to 11...

When I was just a wine drinker, during conversations about wine, when evaluating wine, I kept coming back to the same thing, that more concentrated wines, with darker color were to my mind superior. There were often exceptions, but there seemed to be a clear correlation. My sommelier friends would talk of more esoteric qualities (often that I recognized as wine faults) or a certain refinement that a given wine should possess, but I felt that quality in red wines was about the amount of phenolics.

So in my amateur winemaking, I sought ways to maximise the phenolics. From reading Hugh Johnson's excellent The Vintner's Art, I learned that Bordeaux and Burgundy wine makers routinely do a saignier to their wine, bleeding off 10% - 40% of the juice from the freshly crushed red grapes to make a darker, and more intensely flavored wine. These techniques worked beautifully, in making a magnificently dark, and rich couple of vintages of Cabernet. I was also fortunate to buy outstanding grapes from wine pioneer Ted Gerber, of Foris Vineyards, in Oregon's remote town of Cave Junction. 1991 -1992 was part of a long El Nino, and was lucky too, that Solar Cycle 22 (even larger than our last Solar Cycle 23, which was larger than our current Solar Cycle 24) also peaked at the same time.

Our Bible

El Nino (Gold) / La Nina (Blue) for the last 70 years. This cycle has a huge effect on west coast vineyards in Oregon and California (El Nino - good and La Nina - bad), and less impact on Eastern Washington’s more continental climate.

Then I encountered The Wine Spectrum, a book by an Australian wine scientist, Chris Somers, who devoted his life to studying wine phenolics. The hypothesis of the book is that red wine quality can be objectively determined by measuring the level of phenolics, the more the better, assuming that the underlying wine matrix (water, acidity, alcohol) is sound. This confirmed my gut feeling that the phenolics were the main determinant of red wine quality.

The book also gave me the last piece I was missing as a winemaker - an understanding of the role and importance of pH in red wine. It also explained why my amateur rose wines were so bad - from high pH (low acid).

how we make RED wine Differently

Saignier - To bleed-off a portion (10 - 40%) of the colorless juice immediately after crushing red wine grapes. This makes a more intensely colored wine with more mouthfeel, aroma, and aging potential. Almost all of the great wines Bordeaux and Burgundy have some amount of saignier. It isn't widely talked about because most wineries prefer their customers, wine experts and media completely clueless about how wine is made! The bled-off juice is made into a rose wine. This is a rare example of Less being More.

Sparging - Boiling off Hydrogen Sulphide and other dissolved gas from freshly fermented wines, or wine that has just completed malolactic. This prevents mercaptan and other noxious sulphur compounds from getting a foot-hold in young wine. It also helps eliminates excess diacetyl (butterscotch aromas) after malolactic. It is done with inert Nitrogen gas, bubbled through a carbonating stone, which squeezes out gasses dissolved in wine or must, but does not itself remain dissolved in wine.

Low pH - Many winemakers are taught to acidulate (add acid) to wines near bottling time, as a final adjustment, at the last moment. This is totally wrong. It is like vaccinating your children after they reach adulthood. The optimum time to adjust acidity is at crush, using just tartaric acid. This ensures clean fermentations, with only minimal sulphites at crush, and allowing the young wine to be naturally protected by the bacteria-inhibiting acid. With a good, low pH, minimal sulphites are also required over the wine's time in the tank or barrel.

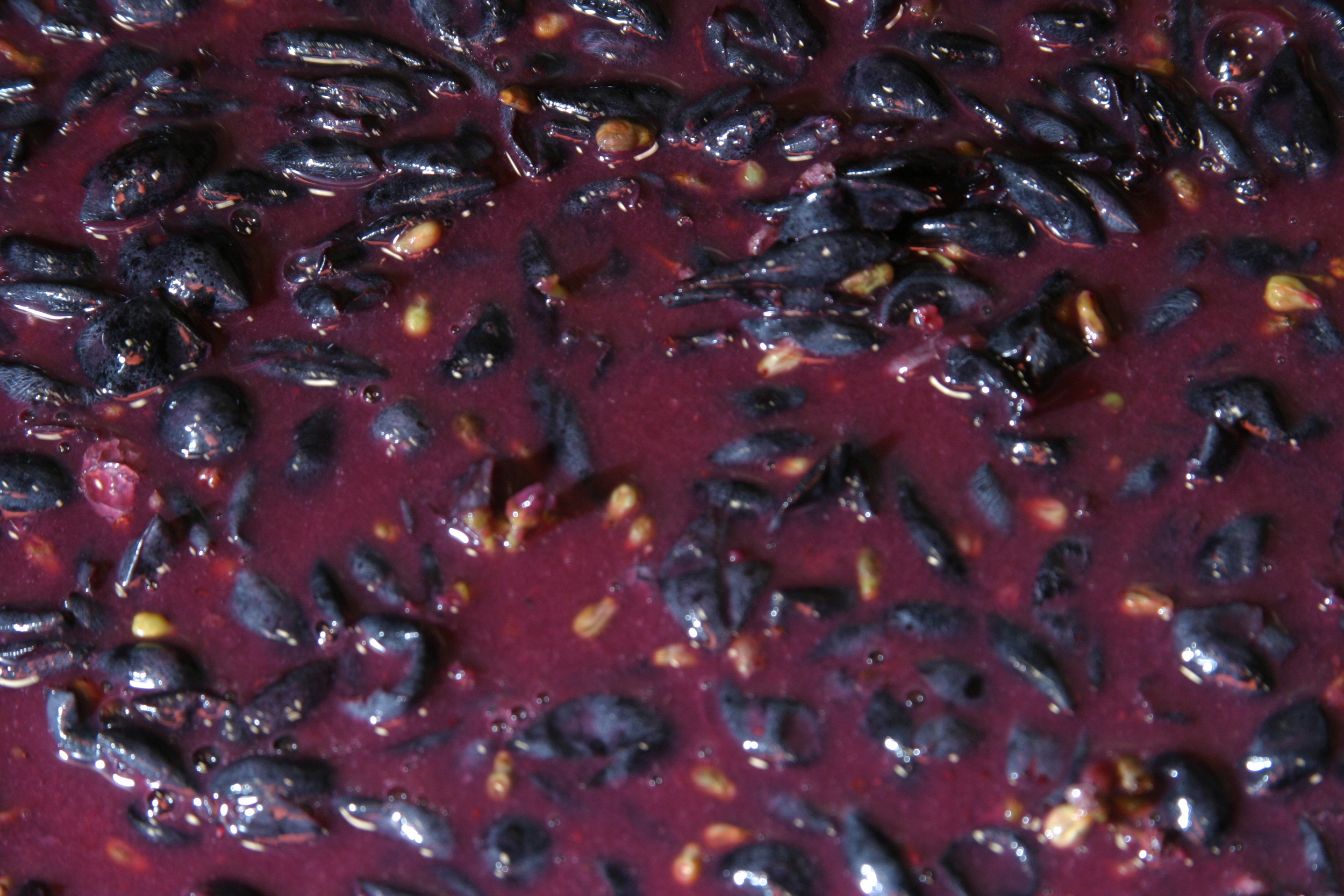

Maximal Extraction - We try and extract as much grape skin phenolics as possible - this is the essence of the vintage - it is almost everything that the wine tastes of - it is easy for a winemaker to leave large amounts of phenolics in the skins - and that is a waste. We use D254 yeast (Scott Labs) that helps extract color, and is a good flocculator. We also use Color-X enzyme (also Scott Labs) to extract the color from the skins before alcoholic fermentation gets rolling. This requires a rapid increase of must temperature, immediatly following a cold soak of 24 - 48 hours. The temperature is raised to 70 - 80 degrees F, making the enzyme’s effectiveness maximal. Once alcoholic fermentation gets going, color is very hard to extract from skins. With a successful fermentation, after about the seventh day, I can easily rub off almost all the color from the skin. This is also from the skins floating up into a thick, warm cap, repeatedly, after frequent punching down. Without the enzyme induced procedure before fermentation, much of the color (and fruit flavor) will remain trapped in the skins, and there is nothing the wine maker can do.

We Use our Own Barrels - I have mastered a technique to restore our French Oak hogsheads (300 L), originally purchased from Nadalie, to be as good as new, or perhaps even better. When I have completed restoring the barrels they have increased surface area of freshly toasted surfaces oak. These barrels have produced two Double Gold winning wines!

No Must Dilution - There is something perverse going on in the Washington wine industry - wine-makers are allowing their red grapes to ripen to extreme brix levels (26 - 28 degrees). They do so under the pretence that they are allowing the tannins or phenolics to ripen more fully. In actuality, this is done because it leaves the winemaker no option but to add copious amounts of (acid-adjusted) water to his must, or otherwise the fermentation would "stick" at about 16% alcohol - the approximate threshold that yeast can survive. The stuck wine must would have lots of residual sugar - and because of that would be unstable. The added water increases the yield of wine substantially - at the expense of quality. If your intentions are to make a wine with a conventional alcohol levels why would you do this?

In an excellent vendange in Bordeaux, using clones of the exact same grapes, and at the same latitude as Eastern Washington, somehow the Bordelaise feel content harvesting the grapes at 24.5 brix (14% Alcohol). They somehow feel that their grape's phenolics are perfectly ripe, and that Mother Nature has been generous to them in such a growing season. In contrast, many winemakers in Eastern Washington, taking advantage of the Cascade strata-volcanoes that shield their vineyards from adverse fall weather, (while Bordeaux is exposed to the North Atlantic Ocean) deliberately allow their grapes to ripen well beyond the Bordeaux norm.

The end result of diluted must wines are wines that are devoid of astringency - mouth-feel. They are also lacking in acidity typically, because of the large amounts needed be added to account for the water, and for the fact that the acid has plummeted in the grapes while on the vine. When you look at the rim of such a wine, you will see a watery-glycerine edge, and a premature brownish cast from over-ripening, giving the appearance that the drink was reconstituted in the glass like a cola from concentrate. It has the same appeal.

Must dilution is something that should be done (it is perfectly legal in the U.S.) when you have no other option - not by design. What is equally disturbing is that many super-premium Washington wineries are guilty of the same practice - they brag of their 28 degrees brix grapes! There can be no other conclusion from such an admission - they dilute their must. The only other possibility is that they are partially de-alcoholising the wine after fermentation - but it would be most likely a combination of the two.

I could see consumers growing weary of such deliberately watered-down wines, (especially when it is happening at both the highest and lowest price levels) and becoming disillusioned with Washington red wines, and wondering what they every liked about them in the first place.

Plastic Corks - Our first 6 vintages of Deluge were all sealed with Supreme Corqs. These closures were the absolute best. I have opened wines from 2002, and the closures are like the day they went in the bottle. We now use other plastic corks - which will not taint our product, leak, or fail, allow air into the wine, dry out, etc. All bark corks react with and therefore, inevitably flavor the wine. The advantages of plastic over bark cork are numerous. We have also used Vinova, and Nomacork, and now Jelinek.